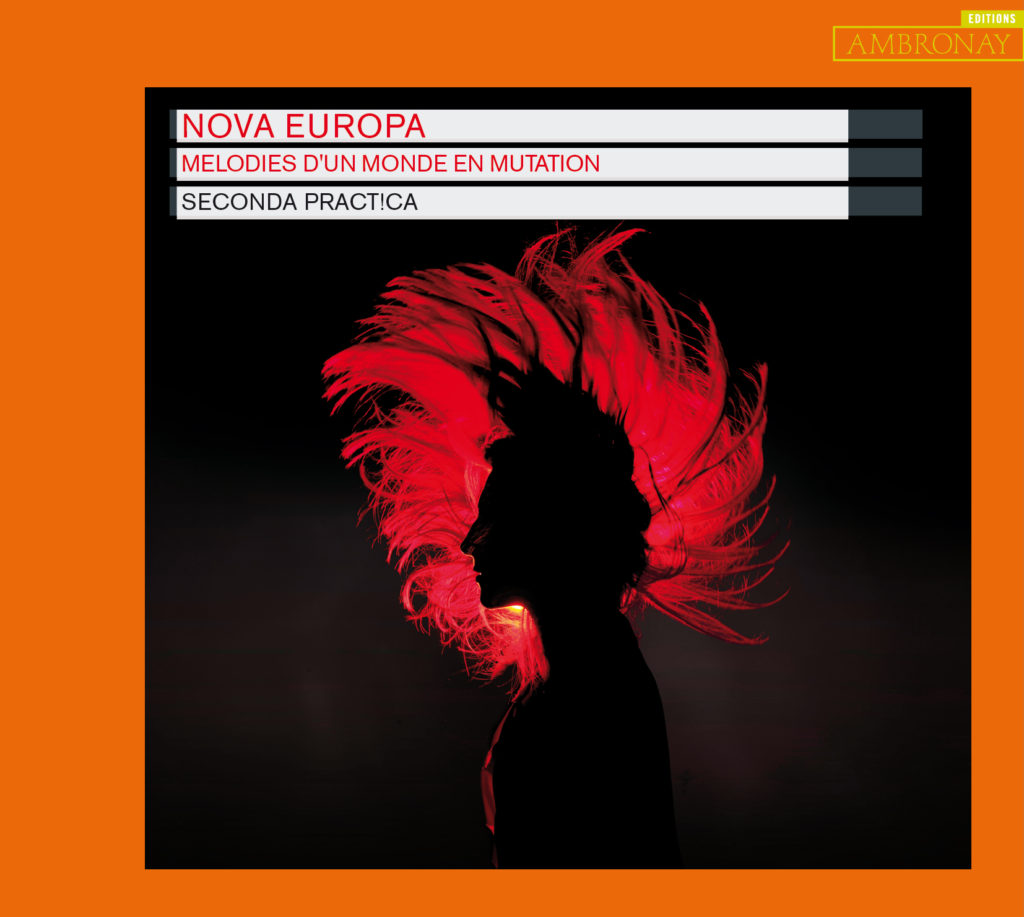

Melodies of a world in formation.

A recording for the label Ambronay Éditions.

From 1492 onward – now that it could no longer be ‘the world’ – Europe wished to become ‘the center of the world’.

A century later, only a few thousand of the twenty-five million indigenous inhabitants of Mexico still survived. The Andean population diminished by 80% in thirty years. After this, cultural domination succeeded physical combat. On each temple that had been destroyed, a church must be built. In each mind, the Christian faith must be instilled by means of art and music; for faith is difficult to transmit by force of arms. It was at this time that the utopia of the Jesuit reductions grew up amid the ruins. In addition to evangelising the natives, the Jesuits also wished to protect them from enslavement by the Spanish colonists.

The paradox is one of major proportions: born in appalling conditions, in the midst of destruction and massacres, the music of the colonial Baroque is studded with masterpieces.

This ethical, political and musical relationship between Europe and colonised South America lies at the heart of the project of the ensemble Seconda Prat!ca.

Available on Spotify!

FOUR FACES OF COLONIAL MUSIC

Each section of our recording contains pieces written by different composers in a variety of times and places.

‘We have assembled here pieces composed in different social and cultural contexts. On one side of the Atlantic, the compositions by Juan de Castro and Étienne Moulinié, who were respectively in the service of the courts of Spain and France, represent European culture.

On the other, the anonymous works drawn from the manuscripts of the Codex Zuola of Cusco, the former capital of the Inca Empire, represent the result of the hybridization between the two cultures.

Michel Montaigne, On the Cannibals

Or, je trouve, pour revenir à mon propos, qu’il n’y a rien de barbare et de sauvage en cette nation, à ce qu’on m’en a rapporté, sinon que chacun appelle barbarie ce qui n’est pas de son usage ; comme de vray il semble que nous n’avons autre mire de la verité et de la raison que l’exemple et l’idée des opinions et usances du païs où nous sommes.

Là est tousjours la parfaicte religion, la parfaicte police, parfait et accompli usage de toutes choses.

Returning to my subject, I find that there is nothing barbarous or savage about this nation, to judge from what I have been told, except insofar as everyone calls barbarous what is contrary to their own usage; just as, in fact, it would appear that we have no other yardstick for truth and reason than the example and model of the opinions and customs of the country where we are situated.

It is always there that one finds the perfect religion, the perfect government, and the perfect and most consummate way of doing everything.

In Chiquitania (now in Bolivia) the Jesuits built “reductions”, a sort of ideal city inspired by thephilosophers of the sixteenth century. As well as anchoring a symbol of Christianity within the city, the churches built by the Jesuits in the reductions combine European architecture with local traditions.

We can observe a similar phenomenon in music, which for the Jesuits had a concrete function. It was performed for and by the population with the aim of transmitting religious faith.

Report of the Mission of Our Father Saint Ignacio in California (1728)

“No faltan de missa los días que les cabe de obligación. Todos los días, assí que se lebantan, que es bien temprano, saludan a Jesuchristo y a su Madre santíssima, cantando el Alabado que rezan los españoles.

Después (…) un catequista de los varios que tienen cada pueblo, les hace una plática doctrinal. Antes de acostarse, rezan, otra vez, el rosario por piedad e instincto proprio de ellos y hacen su acto de contricción.“

‘They never miss Mass even on the days they are not obliged to go. So every day, they rise, at an early hour, and greet Jesus Christ and his Holy Mother, singing the Alabado that the Spanish pray.

Afterwards (…) one of the many priests that each village has, they attend a doctrinal sermon. Before bed, once again they pray the Rosario, that they are granted the instinct and piety proper of them, and they pray their act of contrition.’

Although the Europeans, having colonised South America, forced the survivors to absorb the culture they brought with them, traces of the indigenous peoples’ original culture still remained. A process of creolisation had taken place. Édouard Glissant regards creolisation as a blend of art or language that produces something unpredictable, unexpected.

That manner of transforming oneself without losing oneself, which can be heard in this section, the most folkloric part of the programme, opened the way to a shifting and inextricable culture, a multiple culture that disrupted the standardisation of the great artistic and cultural centres.’

P. António Vieira – Sermon for the Twentieth

“Não há escravo no Brasil, e mais quando vejo os mais miseráveis, que não seja matéria para mim de uma profunda meditação. Comparo o presento com o futuro, o tempo com a Eternidade, o que vejo com o que creio, e não posso entender que Deus, que criou estes homens tanto à sua imagem e semelhança, como os demais, os predestinasse para dois Infernos: um nesta vida, outro na outra.

Isto é o que vos hei-de pregar hoje para vossa consolação.”

There is no slave in Brazil, and even more so when I see the most miserable among them, which is not for me a source of profound meditation. I compare present to future, time to eternity, what I see to what I believe and I cannot conceive that God, who has created these men, like all others, in His image and resemblance, could have doomed them to live twice in hell. The first in this life, the second in the one beyond.

This is what I shall preach today for your consolation.

In order to provide South America with places of worship, the architectural and institutional format of the European cathedral was exported. The sacred rituals and the music of the liturgy crossed the Atlantic along with the plans and architectural skills needed to build these edifices.

In the same way the link between text and music reaches its most intense. The Jesuits met the expectations of the faithful by incorporating into the sacred musical forms, stereotypes borrowed from street songs and especially from the theater: the result is a dialogue in music among several characters, in the age-old form of the responsory.

Yaita-Ki Chronicle, c. 1545

西南蛮の人々は、ある程度優等劣等の区別はつくようであるが、正しい礼儀作法を心得ているかどうか は分かるところではない。

彼らは箸を使わず、手で物を食べ、感情を抑えることができず、我々の言葉を理解もしない。

彼らは定まった住まいもなく、ここかしこと彷徨って暮らし、無いものは物々交換で賄っているようだ。

とはいえ、決して害のある人種ではないように見える。

‘These men are barbarians!

They understand to a certain degree the distinction between Superior and Inferior, but I do not know whether they have a proper system of ceremonial etiquette.

They eat with their fingers instead of with chopsticks such as we use. They show their feelings without any self-control. They cannot read or understand written characters.

They are people who spend their lives roving hither and yon. They have no fixed abode and barter things which they have for those they do not.

But withal they are quite harmless.