21 Sep When does a Concert become a Narrative?

As part of the celebrations of the 2016 European Day of Early Music, we invited a series of renowned specialists to write a statement inspired on the question ‘When does a Concert become a Narrative?’. This statements were then read and debated on a roundtable discussion, involving not only our extraordinary panel but also a very diverse and engaged audience.

Dr. Jed Wentz’s statement resonates in a very special way with everyone that have had the privilege to be taught by him. It also summarizes in a very clear, succinct way a central topic on the field of Historically Informed Theater: the sociology of historical audiences and its effects on the music and the performers of the past.

A version of this article including the quotations in their original language together with their sources, can be found here.

The question of when a concert becomes a narrative cannot be answered, I believe, before a different question has been addressed: where does a concert become a narrative? To this, let me propose an answer: a concert can only become a narrative in the minds of a receptive audience. Without a well-prepped listener, one who believes that a succession of musical events can actually resemble sustained spoken story-telling, even the most carefully programmed concert will be a diegetic disaster.

The good news for fans of the narrative concert is that this audience currently exists, indeed flourishes, in the Classical music scene.

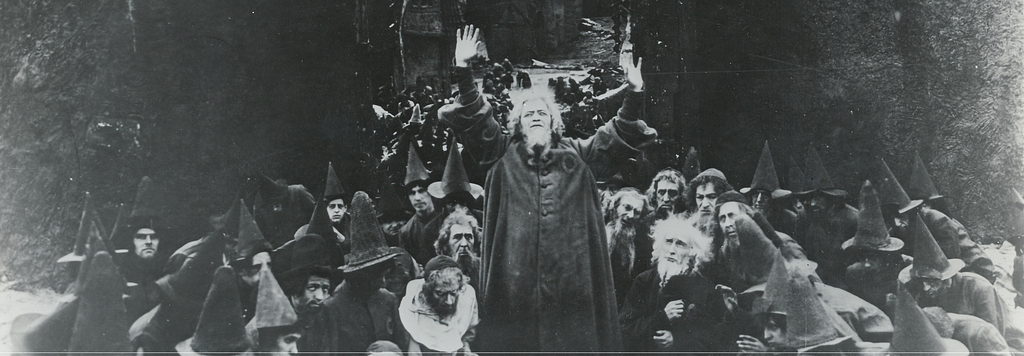

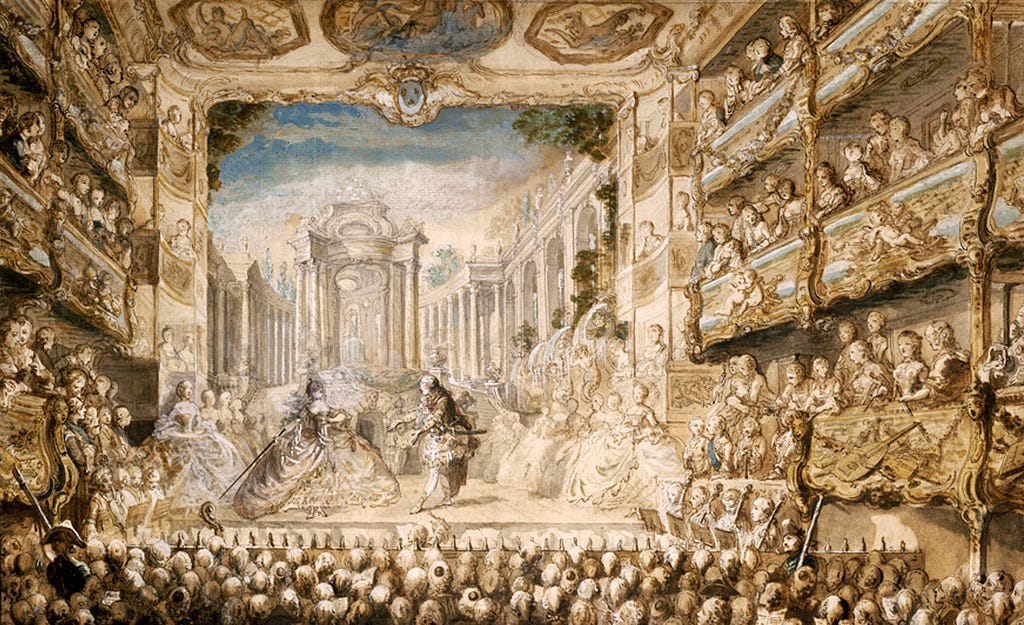

Period sources indicate that audiences of the past did not listen in a sustained way to either theatre, opera or music- so an imposed narrative would have been lost on them. But, with the passage of time, audiences have been tamed, and shamed and trained into obedient silence. This occurred in the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries; and today we continue to embrace the resulting subservient behavior. Having acquiesced to sit in the dark and exclusively listen at concerts, audiences came to expect coherent and consistently polished performances, rather than the 18th-century performative events that were characterized by great unevenness: by high and low points both in performance and in audience behavior.

H. L. Berckenhoff described the process of audience tame-shame-and-train, as it played out in Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw in the late 19thcentury, like this:

[The conductor of the Concertgebouw orchestra], Willem Kes was the man who introduced a new age. Not only was he able to form the orchestra, as far as is humanly possible, into the technically perfect and extremely sensitive instrument that we still admire, he also formed an audience worthy of such an orchestra. What would have been the use of an orchestra capable of the most subtle nuances of timbre and of the reproduction of the most refined rhythms if he had not also impregnated [his] audience with the realization that the concert hall is a place that demands in the visitors a silent attention and energized mind?

His task was not the most rewarding. To bring order in chaos always results in objections to be overcome. One must intervene with a firm hand. Both orchestra and audience lacked discipline. […] We remember him with great gratitude as the creator of a new orchestra and a new audience!

Here we see, at the dawn of the 20th century, both performers and audience ‘rising to the occasion’, as new disciplined listening created a need for more nuanced and subtle performances. But if the listening techniques of just over 100 years ago were so different from those of today, how can we even imagine what a visit to the theatre, the opera, a salon-concert in the 18th century was really like?

Much ink has been spilled over this question; I do not pretend to be breaking new ground here. William Weber’s 1997 article ‘Did people listen in the 18th century?’ pleaded for the allowance of nuances in our conception of historical listening: rather than a black and white understanding of the audience-expectations of the past, an ‘on’ or ‘off’ approach to listening, Weber imagined a fluid state in which audience members and performers received attention by turns. And indeed, there is plenty of evidence of rowdy audience behavior in this period, behavior that must have been far more entertaining than what was going on onstage: Tiffany Stern in Rehearsal from Shakespeare to Sheridan and Jeffrey Ravel in The contested parterre paint lively pictures of, for us, entirely unacceptable audience behavior in Paris and London. Ravel notes of the spoken theatre in Paris:

The spectators in the pit were not consumers of cultural products in the sense that theatregoers are today; they did not necessarily focus their undivided attention on the activity on the stage for three hours to render a verdict determined by their socioeconomic worldview […]. Instead, it appears that they milled about the parterre, interacting with each other and with spectators in other parts of the hall, all the while keeping track of the onstage performance. The performers, in turn, did not require or assume the silent, rapt attention of the spectators.

What is important to note here is that such ‘milling’, ‘interacting’ audiences enjoyed particularly intense moments of listening amongst the myriad ‘distractions’ of a night at the theatre, and that the general chaos heightened rather than diminished their pleasure. That at least was Diderot’s take on the subject. In his Réponse à la lettre de Madame Riccoboni, Didereot laments the fact that by the mid-18th century armed soldiers had been placed on the stages of the Paris opera and the Comédie Française, in order to tame the audience:

Fifteen years ago our theaters were tumultuous places. Upon entering the coolest heads were heated and sensible men shared more or less the deliriums of the insane. […] One was agitated, one was stirred, one was jostled, the soul was beside itself. However, I do not know of a more favorable disposition for the poet. The play got started with difficulty, was often interrupted: but, was there a beautiful passage? [Then] there was an unbelievable fracas, the encores were demanded endlessly, one felt a religious fervor for the author, for the actor, for the actress. The enjoyment passed from the pit to the stalls, from the stalls to the boxes. One arrived [at the theater] hot-headed and went away drunk; some visited prostitutes, others dispersed themselves in society; it was like a tempest that dissipated itself at a distance and which rumbled on for a considerable time after its removal. Voilà le plaisir. Today one arrives cold, listens cold, leaves cold… and I don’t know where one goes afterwards.

Here Didierot claims that a theatre experience predicated on intense listening at literary highpoints mixed with constant irritation and distraction is an ideal one. How different from Berckenhoff’s refined performers and listeners in the Concertgebouw!

Therefore, my conclusion is that:

A concert becomes a narrative when it is subjected to the ideals of late 19th- and early 20th-century concert organizers. If one is performing repertoire from this period, I mean from the late 19th- and early 20th-century, or if one is performing repertoire from any period without attempting to grasp at its original intent, its authenticity, then this might indeed be an interesting way to organize a programme. However, within the context of Early Music, and of authenticity, it is a highly misguided one.

Of course authenticity is a chimera, and we need not chase that rainbow any further here today…but I would like to point out that one of the main reasons that it is a chimera is that no matter how authentic any performance of ours might be, the audience of today decidedly does not behave as it did in the past.

Jed Wentz

March 21, 2016

Amsterdam

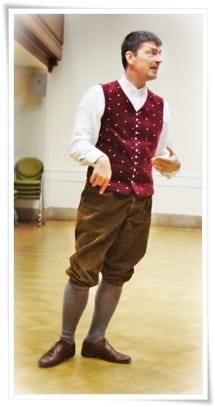

Jed Wentz’s work revolves around the historically informed performance of music written before 1800. He is professionally active as a performer, a teacher and a researcher.

He had played with major Early Music ensembles such as Musica Antiqua Köln and Les Musiciens de Louvre among many others. He recorded more than 30 CDs, as flutist and conductor, many of them with his own ensemble Musica ad Rhenum. He is one of the main subject teachers of Baroque flute at the Conservatorium van Amsterdam, and he also teaches general classes related to Early Music performance practice and history. He currently teaches rhetoric at The Royal Conservatory in The Hague, and he is a guest lecturer at The Juilliard School.

His also a renowned, published scholar, focused mainly on 17th- and 18th-century acting and oratorical styles and their implications for musical performance.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.